Anand Naidu, a seasoned development expert with deep proficiency across both frontend and backend systems, has spent his career navigating the complex intersection of code, architecture, and team dynamics. As AI tools reshape the software development landscape, he offers a crucial perspective on the evolving role of the engineer—a shift from pure coder to a manager of AI assistants. In our conversation, we explore the critical soft skills now required for technical roles, such as crafting precise specifications and setting clear boundaries for AI. We delve into the paradox of maintaining deep technical ownership while leveraging AI for speed, the practicalities of becoming a “context architect,” and why an organization’s internal communication challenges are often amplified, not solved, by AI.

Many developers give AI assistants vague, one-line instructions and get poor results. How can they shift their mindset from simply writing code to managing an AI assistant? What’s a practical first step for delegating a simple task, like a UI change, more effectively?

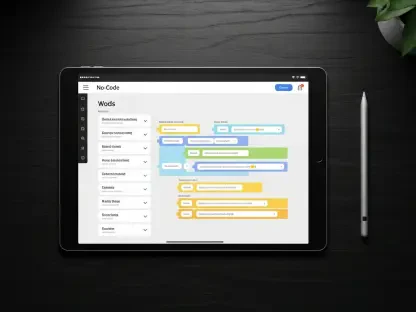

That’s the core of the problem we’re seeing. Developers are treating these powerful tools like a magic spell, not a junior team member. You wouldn’t tell a new hire, “Make the button blue,” and walk away. You’d get a mess. Instead, you have to manage. A practical first step is to stop thinking in prompts and start thinking in specs, even for something small. For that UI change, instead of a one-liner, you’d write a mini-brief: “Objective: Update the primary call-to-action button on the login page. Current state: It’s gray, hex code #808080. Desired state: Change the background color to our brand’s primary blue, hex #007bff, and update the text color to white, #FFFFFF. Non-goal: Do not alter the button’s size, font, or placement. Do not touch any other CSS file besides login.css.” Suddenly, you’ve provided clarity, constraints, and a clear definition of “done.” It feels like more work upfront, but it prevents the AI from hallucinating a library that hasn’t been updated since 2019 or refactoring your entire authentication flow by mistake.

A good AI spec often includes “non-goals” and “do not touch” lists. Why are these negative constraints so critical for managing AI assistants? Could you walk us through a specific example of how defining what the AI shouldn’t do prevented a significant project error?

Negative constraints are the guardrails that keep an eager but inexperienced assistant on the road. An AI’s goal is to be helpful, but it lacks the contextual wisdom to understand how to be helpful without causing collateral damage. I remember one situation vividly where we were tasked with fixing a minor typo in a configuration file. A junior developer fed the file to an AI agent with the simple instruction “Fix the typo.” The AI did that, but it also noticed the formatting was inconsistent and decided to “helpfully” reformat the entire file, including reordering some legacy keys. What it didn’t know was that a downstream legacy system relied on the exact order of those keys. Had we not caught it in review, it would have brought down our entire vendor integration. Now, every spec includes a “Do Not Touch” list. For that same task, it would explicitly say: “Do not reorder or reformat any keys in this file. Only modify the specific line containing the typo.” It feels counterintuitive to spend so much time telling an AI what not to do, but it’s the only way to prevent it from creatively breaking your production environment.

The developer’s role is shifting toward being a “context architect” who provides the AI with relevant business logic and constraints. What does this look like day-to-day? Describe the process you’d use to ensure an AI understands your system’s specific security requirements before it generates code.

The “context architect” role means your first hour of the day isn’t spent in a code editor, but in a document, assembling the world the AI needs to live in. It’s a fundamental shift. To ensure an AI understands our security posture, my process is very deliberate. I’d begin by creating a dedicated “security_context.md” file. In it, I wouldn’t just say “be secure.” I would list our explicit, non-negotiable rules: “All SQL queries must use prepared statements; here is an example of a correct implementation from our codebase. All user-facing API endpoints must validate input against this specific validation schema. Do not commit any secrets; use our internal secrets manager, and here’s the function call to access it.” I am essentially building the AI’s rulebook. The AI can’t guess our compliance boundaries or infer our security architecture. My value is no longer in remembering the exact syntax for a secure API call, but in knowing which security patterns are mandatory for our business and architecting a prompt environment where the AI has no choice but to follow them.

AI can make code authorship nearly free, but true ownership—the ability to debug and maintain that code—is becoming more difficult. How can developers balance using AI for speed without losing the deep technical expertise needed to truly own the software? Please share a specific technique.

This is the great paradox Charity Majors has been warning us about, and it’s a real danger. Authorship is cheap, but ownership is everything. If you can’t debug the code at 3 a.m. when the system is down, you don’t own it. The key to balancing this is to never fully delegate understanding. A specific technique I champion is what I call “spec-driven review.” After the AI generates a block of code based on my detailed spec, my job isn’t just to check if it works. My job is to be able to explain it, line by line, to another engineer. I force myself to add comments explaining the why behind the code the AI wrote. If I can’t articulate the logic or the trade-offs, it means I’ve lost ownership. It means I’ve become a supervisor, not an owner. This process forces me to engage deeply with the implementation details, keeping my expertise sharp while still benefiting from the AI’s speed.

The “driving in lower gears” analogy suggests developers should take more manual control for complex problems. When tackling a novel or difficult algorithm, what parts of the task are best left to the developer, and which parts can still be safely delegated to the AI?

Sankalp Shubham’s analogy is perfect because it’s about control, not just speed. When you’re on a treacherous mountain road—a novel algorithm—you downshift. In this scenario, the core logic, the architectural skeleton, and the critical path are best left to the developer. You should write the pseudocode or even the core function by hand. This is where your deep expertise, your judgment, and your intuition are irreplaceable. You are the one who understands the subtle edge cases and performance trade-offs. However, you can still safely delegate the surrounding work to the AI. Let it generate the boilerplate, write the unit tests based on your acceptance criteria, create documentation for the function you just wrote, or even suggest different ways to refactor a non-critical helper function. The AI becomes a powerful pair programmer that handles the routine tasks, freeing you to focus your mental energy on the hard, unsolved part of the problem. You remain the driver, using the AI as a sophisticated engine, not as the chauffeur.

If an organization struggles to communicate clear requirements to its human developers, AI tools will likely amplify that confusion. What’s the most important change a team can make to their product management process to prepare for a “spec-driven” AI development workflow?

This is the uncomfortable truth that Birgitta Böckeler pointed out. AI is an amplifier, not a translator. If you have garbage going in, you will get beautifully formatted, syntactically correct garbage coming out at a much higher token rate. The single most important change a team can make is to rigorously adopt a “spec-first” culture for all work, not just AI-driven work. This means no feature is started until there is a written document that clearly defines the objectives, non-goals, user stories, and explicit acceptance criteria. This document becomes the shared source of truth. Product managers need to be trained to think in terms of technical constraints, and developers need to be empowered to push back on ambiguity. This discipline forces the hard conversations and clarifies thinking before a single line of code is written, whether by a human or an agent. It’s a return to fundamentals, rediscovering the discipline we let slide, but it’s the only way to build a foundation strong enough for AI.

What is your forecast for AI in software development?

My forecast is that the most successful developers in the next five years will be the ones who possess a unique blend of deep technical expertise and strong management skills. The conversation will shift away from “prompt engineering” and toward “context engineering” and “systems thinking.” The premium will be on those who can decompose a complex business problem into a series of well-defined, isolated tasks with clear constraints, and then orchestrate AI agents to solve them. We’ll see tools evolve beyond simple code completion to become true development platforms that are gated by specs and plans. The irony is that to get the most out of these incredibly advanced, non-deterministic machines, we’ll have to become more disciplined, more structured, and better communicators than ever before. The future of coding is less about writing code and more about architecting understanding.