The frustrating reality for many scaling software companies is that their single, shared development environment, once a symbol of collaborative simplicity, inevitably transforms into a digital battlefield where progress is the primary casualty. This common challenge faced by growing engineering organizations is not merely an inconvenience; it represents a fundamental drag on productivity, innovation, and speed to market. For ClassPass, this scenario reached a critical point when over 90 engineers found themselves in a constant tug-of-war for resources on one Amazon ECS development cluster. Deployments from one team would frequently overwrite the work of another, breaking builds, invalidating tests, and grinding progress to a halt for backend, frontend, and mobile teams alike. This article details the ClassPass journey, exploring their evolution from a series of well-intentioned but ultimately flawed solutions to a successful dynamic routing architecture that finally enabled true parallel testing, transforming a bottleneck into a force multiplier.

The Developer Bottleneck: When a Single Test Environment Grinds Productivity to a Halt

A congested development pipeline is far more than a source of developer frustration; it is a direct impediment to business growth, delaying product delivery and stifling the innovation necessary to stay competitive. When engineers spend more time waiting for a clear testing window or debugging environment-related failures than writing code, the entire product lifecycle suffers. ClassPass’s journey from a single, contended environment to a model of parallel efficiency illustrates how solving this problem can yield transformative results across an organization. This case study explores their path, highlighting a series of failed attempts that provided crucial, hard-won lessons before culminating in a sophisticated yet pragmatic solution. The narrative is not just about a technical fix but a sociotechnical evolution that required a shift in mindset and a deep understanding of developer workflows. By dissecting their failures and ultimate success, other organizations can find a blueprint for escaping the common pitfalls of a shared testing environment.

The central problem at ClassPass was a systemic bottleneck created by its reliance on a single ECS development cluster, which served as the sole proving ground for all pre-production testing for a diverse group of over 90 engineers across backend, frontend, and mobile development teams. The nature of this shared resource meant that multiple teams were constantly competing to deploy different versions of the same microservices. This created a state of perpetual contention, where one team’s deployment could inadvertently break the environment for everyone else. The result was a cascade of negative consequences: broken builds became a daily occurrence, tests conducted by one team were invalidated by another’s deployment, and developer velocity plummeted. The environment became a source of friction rather than a tool for acceleration, forcing engineers into a reactive mode of operation and severely limiting the organization’s ability to test and iterate quickly.

This article serves as a case study in overcoming a deeply ingrained infrastructural challenge and chronicles the evolutionary process ClassPass undertook, moving from initial attempts that failed to address the core issue to a final, successful architecture built on dynamic routing. Their story is a powerful testament to the idea that complex engineering problems often require more than just a technological solution; they demand a holistic approach that considers organizational culture, developer experience, and the practical realities of a constrained budget and lean platform team. The ultimate solution—a system of “shadow mains” and ephemeral environments on a single cluster—did not require a massive, cost-prohibitive infrastructure overhaul. Instead, it leveraged clever routing and context propagation to create a multi-layered testing reality, effectively giving every developer their own isolated slice of the shared environment on demand.

Why Solving Testing Contention Is a Business Imperative

A clogged development pipeline directly impacts developer velocity, product delivery, and innovation, creating a ripple effect that extends far beyond the engineering department. When developers are blocked, the entire product roadmap is at risk. Features are delayed, bug fixes take longer, and the organization’s ability to respond to market changes is severely compromised. This loss of momentum is not just a matter of missed deadlines; it translates into lost revenue, decreased customer satisfaction, and a diminished competitive edge. By addressing the root cause of testing contention, ClassPass unlocked significant business value, demonstrating that investing in the developer experience is a direct investment in the company’s bottom line. Their solution fostered an environment where engineers could work more efficiently, reliably, and collaboratively, ultimately accelerating the pace of innovation.

The implementation of a dynamic routing architecture delivered a suite of key benefits that fundamentally reshaped the development culture at ClassPass; the most immediate impact was a dramatic increase in efficiency. By drastically reducing wait times and eliminating the constant cycle of broken builds, the new system allowed multiple teams to work in parallel without conflict. This meant that a backend developer working on a major service refactor no longer had to worry about disrupting a mobile team testing a new feature. The ability to spin up isolated, ephemeral environments for specific branches meant that testing became a seamless part of the development workflow rather than a scheduled, contentious event. This newfound parallelism directly translated into faster development cycles and a more productive engineering organization.

Moreover, the solution brought a new level of reliability to the testing process, with the concept of a “shadow main”—a stable, continuously deployed version of every service running the latest code from the main branch—providing a dependable baseline for all teams. Frontend and mobile engineers, who had previously been at the mercy of volatile, manually deployed backend services, could now test against this stable environment with confidence. This isolation protected them from the constant churn of feature development, ensuring their own test cycles were not derailed by unrelated backend changes. The result was a more predictable and trustworthy pre-production environment, which improved the quality of testing and reduced the number of bugs that slipped through to production.

The introduction of the “shadow main” also served as a critical foundational step toward accelerating CI/CD adoption. By normalizing the practice of continuously deploying the main branch to a stable, production-like environment, the organization began to build the discipline and technical infrastructure required for true continuous deployment. This “shadow” environment acted as a proving ground, allowing the platform team to harden the automated deployment pipelines and build confidence in the process without impacting the legacy manual workflows that were still in use. It created a practical and evolutionary path toward modernizing their release practices, paving the way for a future where every merge to main could potentially be a release candidate. This strategic move not only improved the testing landscape but also positioned the company for greater agility and faster delivery in the long term.

Finally, the ClassPass solution delivered significant cost savings, not by adding more infrastructure, but by maximizing the use of what they already had. Instead of provisioning dozens of full-stack environments—a costly and operationally complex undertaking—they found a way to create logical separation on a single physical cluster. The primary cost was the engineering time to build and maintain the system, but this was more than offset by the immense savings in lost engineering hours. The reduction in time spent waiting, debugging environment issues, and re-running failed builds represented a massive productivity gain. By enabling engineers to focus on high-value work, the company ensured that its most valuable resource—developer talent—was being utilized to its fullest potential, driving innovation and delivering value to customers more efficiently.

The Path to Parallelism: An Evolutionary Tale of Trial and Error

The final, successful architecture at ClassPass was not the product of a single brilliant idea but rather the culmination of an evolutionary journey marked by significant trial and error. This path of learning from past failures was crucial, as each unsuccessful attempt provided invaluable insights into the organization’s unique constraints and unspoken requirements. The team discovered that the problem was not purely technical but deeply sociotechnical, involving developer habits, cross-team communication, and the need for a solution that could integrate smoothly into existing workflows. This realization framed the solution-finding process as a quest for a pragmatic system that could coexist with legacy processes while paving a clear path toward a more modern, automated future.

This journey required a fundamental sociotechnical shift, emphasizing that technology alone was not the answer, as early attempts to impose a purely technical solution failed because they did not account for the human element—how developers actually worked and what they needed to be productive. The organization had to move from a siloed mindset, where platform operations and product engineering operated independently, toward a more collaborative model. This involved leadership buy-in to prioritize developer tooling, the formation of cross-functional teams to bridge communication gaps, and a collective willingness to abandon old habits. The ultimate success of the dynamic routing system was as much a result of this cultural change as it was the elegant implementation of Traefik and OpenTelemetry. It was a testament to the idea that the best infrastructure solutions are those that are designed with a deep empathy for the people who will use them every day.

Recognizing the Anti-Patterns: What Did Not Work

Before arriving at a workable solution, ClassPass explored several strategies that ultimately failed to solve the core problem of testing contention, but these initial attempts were not wasted efforts. They served as valuable, hard-won lessons that illuminated the anti-patterns to avoid and clarified the essential requirements for any future system. By dissecting these failures, the engineering team was able to build a much deeper understanding of their own development ecosystem, including the hidden dependencies and workflow realities that had been overlooked in previous planning. These experiences became the intellectual bedrock upon which the successful dynamic routing architecture was built, ensuring that the final design was resilient, practical, and tailored to the specific needs of the organization.

The first major attempt to bypass the shared development environment was a homegrown integration testing framework, internally named “FIT.” This self-contained command-line tool was designed to allow backend developers to run a comprehensive suite of tests locally or in a continuous integration environment without ever touching the contended development cluster. The concept was ambitious: FIT would spin up the entire microservice ecosystem on self-maintained Jenkins agents, pulling every service’s Docker image and orchestrating them into a functional test environment. However, this cautionary tale of complexity quickly revealed its flaws. The framework was painfully slow, with setup times often exceeding 15 minutes before a single test could execute. It was also incredibly resource-intensive, frequently causing builds to fail due to network timeouts or resource exhaustion from downloading massive Docker images.

The FIT framework’s failure was multifaceted; its custom Docker orchestration layer was a complex black box, poorly documented and nearly impossible to maintain after its original creator left the company. Developers were burdened with a cumbersome workflow that required managing manual network configurations and submitting separate pull requests for code and test changes. Most critically, FIT failed to solve the problem for the very people who were most affected by the shared environment’s instability: the front-end and mobile engineers. They still needed a live, stable back-end to test against, and FIT offered them no relief. The mock data used by the framework had also drifted so far from production reality that the tests it ran were flaky and unreliable, providing a false sense of security. The eventual decision to turn off the entire FIT suite—which resulted in no discernible increase in production incidents—was a sobering confirmation that it had become a pure productivity drag with negligible value.

Following the failure of local testing, the pendulum swung to the opposite extreme, adopting a philosophy of “testing in production.” The idea was to rely on robust production monitoring to catch issues after deployment, with the assumption that testing against the real system with real traffic was the ultimate form of validation. This strategy, however, proved to be fundamentally incompatible with ClassPass’s architecture. Their production environment was not designed to isolate test traffic from real user data, making any form of pre-release testing a high-risk endeavor. This reactive approach offered no safety net for developers, turning every deployment into a potential fire drill. As the team quickly learned, monitoring is essential for identifying problems that are already happening, but it is no substitute for a proactive testing strategy designed to prevent those problems from occurring in the first place. This failed experiment underscored the high cost of not having a proper testing infrastructure and reinforced the need for a solution that could provide a safe, isolated pre-production environment.

The Core Solution: Dynamic Routing with Traefik and OpenTelemetry

The series of failed attempts led to a crucial paradigm shift: instead of trying to eliminate or bypass the shared development environment, the team decided to embrace it by focusing on a solution that would enable multiple parallel, isolated workflows to coexist within it. This new approach acknowledged the reality that developers needed access to the shared data and infrastructure of the development cluster but also required the ability to test their changes without disrupting others. The goal was to transform the single, monolithic environment into a flexible, multi-tenant platform where different versions of services could run concurrently and be accessed on demand. This conceptual leap from physical separation to logical separation was the key that unlocked the final, successful architecture.

The primary technical blocker to implementing version-based routing was the inherent limitation of the AWS Application Load Balancer (ALB), as the existing architecture relied on ALBs with hardcoded DNS names. This setup worked well for a single version of each service but was wholly unsuitable for dynamic routing. ALBs have a hard limit on the number of routing rules they can support, and with over 80 microservices—many requiring separate rules for HTTP and gRPC—this limit was quickly exhausted. This constraint made it impossible to implement the fine-grained, header-based routing necessary to direct traffic to multiple ephemeral versions of each service. The ALB, once a core component of their infrastructure, had become the main obstacle to progress.

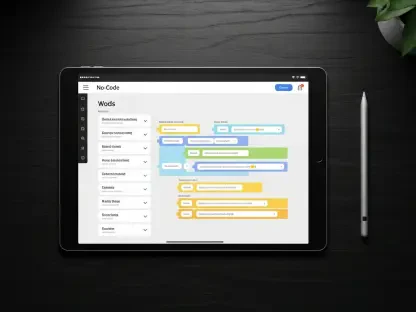

To overcome this infrastructure limitation, the team introduced Traefik, an open-source reverse proxy, to act as an intelligent routing layer in front of the services. This decision to bypass the ALB rather than fight its limitations was a pivotal moment. Traefik’s key advantage was its ability to dynamically discover routing configurations from Docker labels applied to ECS task definitions. This meant that routing logic could be defined declaratively as Infrastructure as Code and managed as part of the CI/CD pipeline. The team configured Traefik to inspect incoming HTTP requests for a specific header. Based on the header’s value, it could intelligently route the request to the correct container: one running a specific feature branch, one running the stable “shadow main,” or the default legacy deployment. This elegant solution provided the complex routing capabilities they needed without requiring a disruptive overhaul of the underlying ECS cluster.

The next challenge was to ensure that this routing decision was maintained as a request traveled through the distributed microservices architecture. If an initial request was routed to a feature-branch version of an upstream service, any subsequent downstream calls it made to other services also had to be routed to their corresponding feature-branch versions. To solve this, the team implemented OpenTelemetry (OTel) Baggage, a powerful mechanism for propagating key-value pairs across service boundaries along with a distributed trace. They used it to carry the routing directive (e.g., dynamic_route=feature-xyz-123) seamlessly through the call stack. The implementation was remarkably straightforward; by simply installing the OTel Java agent, the baggage header was automatically propagated across both HTTP and gRPC calls without requiring any manual code changes from application developers. This “plug-and-play” solution for context propagation was a significant win, making the entire system transparent to developers and easy to adopt.

The New Architecture: Shadow Mains and Ephemeral Environments

The practical outcome of this technical solution was the creation of a multi-layered testing reality on a single cluster. The architecture effectively transformed the monolithic development environment into a dynamic and flexible platform capable of supporting multiple, concurrent realities. The core concepts of this new world were the “shadow main” and ephemeral feature environments. The shadow main provided a stable, always-on version of every service, continuously deployed from the main branch, which served as a reliable baseline for all testing. Alongside it, the system could spin up any number of ephemeral environments, each tied to a specific feature branch, allowing developers to test their changes in complete isolation. This multi-layered approach finally decoupled the teams from one another, allowing them to work in parallel without fear of collision or disruption.

The request flow in this new architecture elegantly demonstrates its power and flexibility. When a request enters the development cluster, it first hits the Traefik reverse proxy, which inspects the request headers for a specific routing directive. If it finds a header indicating a feature branch (e.g., X-Route-Version: feature-xyz-123), it forwards the request to the ephemeral container running the code for that specific branch. If the header indicates “shadow,” the request is sent to the stable, continuously deployed “shadow main” version of the service. In the absence of any specific routing header, the request falls through to the default, manually deployed legacy service, ensuring that existing workflows remain uninterrupted. This tiered routing logic is the heart of the system, providing a sophisticated yet predictable way to navigate the multiple versions of services running on the cluster.

This new capability empowered all engineers—backend, frontend, and mobile—to test against any version of any service on demand. For a backend developer, CI jobs could now automatically spin up an ephemeral container for their branch and run integration tests against it, with OpenTelemetry ensuring that all downstream calls were correctly routed. For a frontend engineer, testing a new feature that depended on a specific backend change was as simple as setting a cookie in their browser to inject the necessary routing header. Similarly, mobile developers could use a debug menu in their app to direct their API calls to a specific feature branch or the stable shadow main. This level of control and flexibility fundamentally changed the developer experience, transforming the testing process from a source of friction into a powerful enabler of speed and quality.

The Verdict: A Blueprint for Scalable Development

ClassPass’s journey from a congested, single-threaded development environment to a parallelized, multi-tenant testing platform provides a pragmatic and effective blueprint for other organizations struggling with similar bottlenecks. Their model demonstrates that it is possible to achieve the benefits of isolated testing—such as increased developer velocity and improved reliability—without incurring the high cost and operational overhead of provisioning dozens of full-stack environments. By cleverly leveraging a reverse proxy and distributed tracing, they created a system of logical separation on shared infrastructure, proving that resource constraints can often be a catalyst for innovative and efficient solutions.

This solution is particularly ideal for engineering teams that have already adopted a container-based infrastructure, such as Amazon ECS or Kubernetes, and are looking to improve developer velocity as they scale. The principles of dynamic, header-based routing and context propagation are platform-agnostic and can be adapted to various technology stacks. The key prerequisites for adoption are a solid organizational grasp of reverse proxy technologies like Traefik or NGINX, a commitment to observability through the implementation of standards like OpenTelemetry, and, most importantly, a cultural willingness to invest in developer education and onboarding. The success of such a system relies heavily on developers understanding how to use the new workflows to their full potential.

Before embarking on a similar path, organizations should consider several key factors as the transition involves not just technical implementation but also a significant sociotechnical shift. Teams must be prepared to educate the entire engineering organization on the new capabilities and foster widespread adoption. There will be technical hurdles to overcome, such as configuring network access for CI runners and addressing architectural gaps like the need for robust, container-level health checks. Furthermore, as ClassPass discovered, solving the environment contention problem often reveals the next bottleneck in the development lifecycle, such as the challenge of managing test data and database migrations in a fully automated CI/CD context. However, by embracing this evolutionary approach, organizations can systematically dismantle barriers to productivity and build a truly scalable and efficient development platform.