Anand Naidu, a leading expert in AI development with deep proficiency across the full stack, has been at the forefront of the shift towards creating more autonomous and capable AI systems. In this conversation, he unpacks the intricate architecture of modern AI agents, moving beyond simple chatbots to explore the engineering feats required for long-horizon tasks. We’ll explore the critical balance between raw model power and the sophisticated “harnesses” that guide them, the emerging paradigm where execution “traces” replace code as the ultimate source of truth, and the surprising ways that giving an agent a simple file system can unlock profound capabilities. Anand will also touch on how agents are beginning to learn from their own mistakes, creating a powerful cycle of self-improvement, and what the user experience of collaborating with these advanced systems will look like.

The success of long-horizon agents depends on both model quality and clever harness engineering. How do you see the interplay between these two evolving? For instance, what specific harness innovations, like compaction strategies or planning tools, are currently providing the most significant performance lifts?

It’s absolutely a combination of both, and they’re evolving in a fascinating symbiotic relationship. You can’t really separate them. The models are getting dramatically better at reasoning, which is essential, but we’re also getting so much smarter about the scaffolding we build around them. This “harness” is what turns a powerful but raw model into a reliable, long-running agent. For instance, we now give these harnesses a built-in planning tool by default, which is a very opinionated choice about how an agent should approach a problem. Another huge lift comes from compaction strategies. As an agent runs for hours or days, its context window fills up. A clever harness knows how to summarize that history or offload it, which is a critical engineering challenge. But perhaps the biggest innovation is giving agents tools to interact with a file system. This wasn’t really possible two years ago because the models weren’t trained for it. Now, models are trained on that kind of data, and the harnesses are built to leverage it. So you see this constant dance: the models get better, which enables new harness techniques, and those techniques then inform how future models are trained.

Coding agents are excelling, partly due to their interaction with file systems. To what extent do you believe all future powerful agents will be “coding agents” at their core? Can you share an example where providing file system access unlocked a surprising or non-obvious capability?

That’s one of the biggest questions we’re grappling with right now. I very, very strongly believe that if you’re building a serious long-horizon agent today, you absolutely must give it access to a file system. The capabilities it unlocks for context management alone are immense. For example, think about our compaction problem. A great strategy is to have the agent summarize its recent actions in its main context window but write the full, detailed logs to a file. That way, if it ever needs to recall a specific detail from hours ago, it can just read the file instead of having to hold gigs of information in active memory. Another non-obvious example is with large tool outputs. If an agent calls an API that returns a massive JSON object, you don’t want to stuff all of that into the precious context window. Instead, the harness can save it to a file and just give the agent the file path. The agent can then open it and parse what it needs. So while a general-purpose agent might be a coding agent, today’s coding agents are still a bit too specialized. The underlying principle of state management via a file system, however, feels universal.

You’ve noted that agent development is fundamentally different from traditional software, with “traces” replacing code as the source of truth. Could you walk us through a specific instance where a trace revealed a critical agent behavior that would have been impossible to find just by reviewing the code?

This is the most fundamental shift in how we build and debug. In traditional software, if something goes wrong, you look at the code. The logic is all there. With an agent, a huge part of the logic lives inside the black box of the model. I can’t just read the code of the harness and predict what the agent will do. A perfect example is when an agent gets stuck in a loop or goes off the rails after running for a while. You might look at the code for the harness, and it seems perfectly fine. The problem isn’t in the static code; it’s in the dynamic context that has been built up over time. A trace shows you everything. We had a case where an agent at step 14 was failing consistently. Looking at the code told us nothing. But when we examined the trace, we saw that a tool call at step 6 had returned an ambiguous result, and at step 10, the agent misinterpreted it, subtly corrupting its own context. By step 14, its entire understanding of the task was flawed. You would never, ever find that by just reading the code. It’s why our response to a bug report has shifted from “Show me the code” to “Send us the trace.” The trace is the only ground truth.

Persistent memory seems key for agent evolution, enabling them to learn from past interactions. How does this “recursive self-improvement” work in practice? Can you explain the process where an agent analyzes its own performance traces to update its instructions and what makes this a defensible moat?

This is where things get really exciting and starts to feel like true learning. It’s a very active area of development, but the core loop is becoming clear. An agent can be given a tool—say, a command-line interface—that allows it to pull down its own performance traces from a system like LangSmith. It can then be prompted to analyze those traces, especially the ones flagged with errors or poor user feedback. The agent literally reads through its past “thoughts” and actions and can diagnose what went wrong. Then, it can use its file system tools to open its own instruction or prompt file and edit it to correct the behavior for the future. For example, if a user gives feedback like, “Instead of doing X, you should have done Y,” the agent can add a new directive to its core instructions: “When faced with situation Z, always prefer action Y.” This creates a real moat because the agent becomes uniquely tailored to its specific tasks and user preferences over time. My own personal email agent is a great example. I moved it to a new platform, and even with the same starter prompt, it felt dumb because it lost all those accumulated memories and self-corrections. It’s that learned experience that makes it valuable.

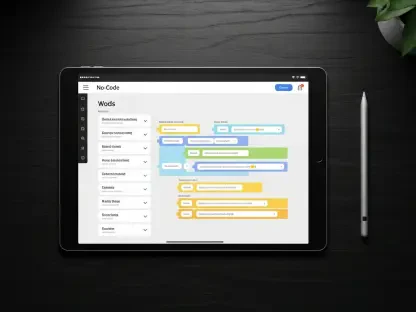

With agents running asynchronously for long periods, their user interface becomes critical. Beyond a simple chat window, what does an effective UI for managing and collaborating with multiple long-horizon agents look like? How do you balance synchronous feedback with asynchronous task management?

The UI has to evolve beyond a simple chat box. You need what I think of as a sync mode and an async mode. For asynchronous management, you’re looking at something more like a project management tool—a Kanban board, a Jira-style dashboard, or even an inbox. You might kick off ten different research agents at once, and you need a central place to see their progress, check their status, and get notifications when they’re done or need help. You’re not going to just sit there and watch a loading spinner for 24 hours. But then, when an agent comes back with a draft report, you need to be able to switch into a synchronous mode. This is where chat is actually quite effective, but it needs to be augmented. Because these agents are manipulating state—like editing a codebase or a document—the UI needs a way to view that state directly. You need to see the files it’s changing, the code it’s writing. The best UIs will feel like a collaborative workspace, maybe like a Google Doc or an IDE, where both you and the agent are present and can act on the same set of artifacts.

What is your forecast for agent development over the next two years?

I believe we’re going to see a major focus on two areas: memory and context engineering. The core algorithm of running a powerful LLM in a loop is surprisingly simple and general-purpose, and we’re finally at a point where the models are good enough for it to work reliably. The next frontier is making that loop smarter. That means more sophisticated tricks for context engineering—giving agents new types of context to pull in, or even letting the models themselves decide when and how to compact their own context. But the biggest leap will be in memory. We’ll move from agents that start fresh with every task to agents that learn over time, both from direct user feedback and by automatically reviewing their own performance traces during “sleep time compute.” This recursive self-improvement will be the key differentiator, turning general-purpose harnesses into highly specialized, expert assistants that build a true, defensible moat through experience.